Approximately 250,000 children suffer burn injuries each year in the United States, accounting for one‑third of all burns. Of these patients, about 30,000 require hospital admission. Pediatric burn resuscitation protocol has improved over the past few decades, but burn injuries remain the fifth leading cause of death in pediatric patients each year (Phillips, 2012).

Toddlers are the most at-risk group for pediatric burns, as their newly acquired mobility and their curiosity to explore their environment places them at a greater risk for burn injury; males are typically more likely to suffer burn injury than females. Scald injuries are the most prevalent pediatric burns for children under the age of five, accounting account for approximately 65% of the cases; fire injury is most common in older children, making up 56% of the cases (Krishnamoorthy, 2012).

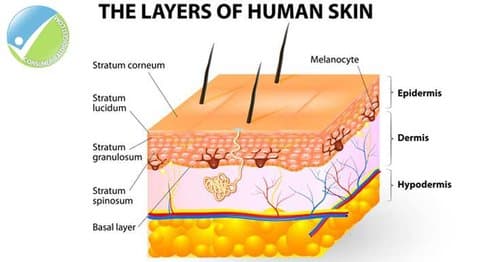

In order to grasp more than a surface understanding of burns, it’s important to have foundational knowledge about human skin. The skin is the largest organ in the human body. It serves multiple functions, including structural support, protection and regulation of heat and water loss. The skin is comprised of three layers: the outer layer called the epidermis, a secondary layer called the dermis and a third layer known as the subcutaneous tissue (or hypodermis). The epidermis is responsible for developing new skin cells, providing immunity and supplying pigment to the visual layer of the skin. The secondary layer, call the dermis, is responsible for sensation, hair growth, sweat production, oil secretion and blood flow. The hypodermis, or subcutaneous fat, attaches the skin to the muscle and bone, controls body temperature and stores fat.

Revised Burn Classification: Understanding Degrees of Skin Damage

The traditional classification of first degree, second degree and third degree burns has been replaced by a more helpful classification system based on the need for surgical intervention. The current accepted burn terminology is superficial, superficial partial thickness, deep partial thickness, full thickness and fourth degree burns.

A superficial burn:

- affects the epidermal layer

- does not progress into the dermis

- is typically recognized as redness to the skin

A superficial partial thickness burn:

- involves the entire epidermis and different parts of the dermis

- typically presents with pain

- includes redness to the skin, which will whiten when pressed

- has blistering

A deep partial thickness burn:

- presents with redness or white coloration to the skin that does not blanch

- has blistering

- typically requires surgical intervention

Full thickness burns:

- affect the entire epidermis, dermis

- have a leathery appearance

The fourth degree burn:

- is the deepest burn

- involves damage to the fascia, muscle, and bone

- almost always require surgical intervention and grafting

Classifications of Burn

SCALD BURNS

As noted earlier, scald burns are the most prevalent pediatric burn for children under the age of five. In many instances, scald burns are accidents that occur in the kitchen due to moments of parental inattention and child curiosity. Typically, spilling a liquid causes a splash or flow type of pattern where the deepest and widest part of the burn are at the first point of contact, with less injury as the liquid flows down the body. With thicker liquids such as oil, grease or even syrup, the burn pattern may be more extensive because these liquids hold their heat longer. Folds of skin may be missing a burn pattern due to the if the child clenched or flexed their limbs.

The burn pattern may be interrupted by diapers or clothing, which may protect the skin. Clothing and diapers can, however, increase the burn injury if the clothing or diaper becomes saturated with the hot liquid and retains the heat.

IMMERSION BURNS

Immersion burns indicate that the child has been in some form of hot liquid, but do not necessarily indicate abuse; these can result from and accidental fall. According to the Burn Foundation (n.d.), hot water causes partial and full thickness burns:

- in 1 second at 156°

- in 2 seconds at 149°

- in 5 seconds at 140°

- in 15 seconds at 133°

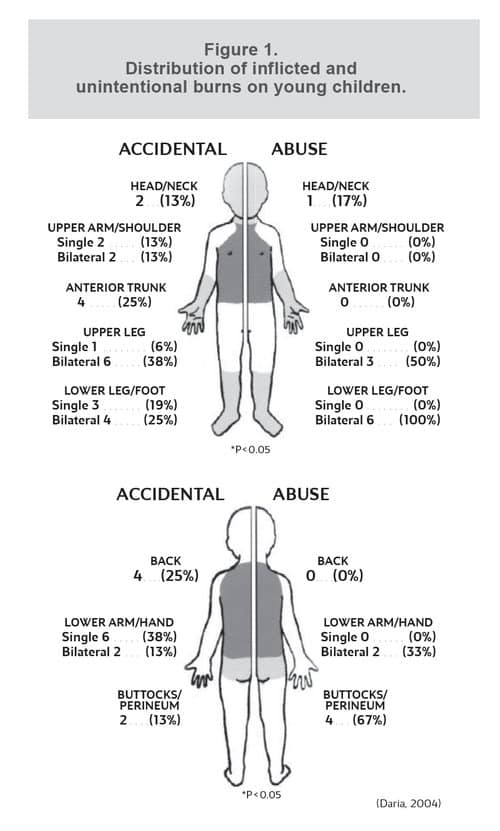

Intentional immersion burns can present with sharp margins caused from the child being held in the hot liquid. The degree of burn is uniform and may have 360 degree involvement. In accidental immersion burns, often splash patterns will be present as the child tries to escape from the hot liquid; however, this may be present in intentional immersions as the child is likely to attempt escape. If a child is immediately immersed into hot liquid and pressed against the bottom of the container or tub, the buttocks may be spared and show no burn. If it was reported, for example, that the child climbed over the bathtub and fell into the water; irregular splash patterns would likely be present in multiple areas of the body. (See Figure 1)

CONTACT BURNS

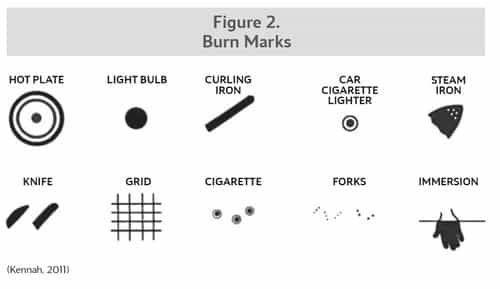

Contact burns, such as with curling irons, furnace grates, irons, stoves, oven doors and cigarettes are common in small children. Accidental burns are more likely to exhibit unclear margins, as the child is trying to escape the object. If an object fell onto the skin, such as when a child pulls on an iron cord, the burn will likely exhibit an unclear margin as the iron briefly hit the skin. Many times contact burns are seen on the palm of the hand due to the child grabbing the object. Intentional burns can also be caused by the above objects, but are likely to reveal a clearer pattern, have distinct margins and may occur on areas normally covered with clothing.

Cigarette burns, in particular, can occur intentionally or accidentally. Accidental cigarette burns can appear elongated, have poorly defined edges and will likely appear as a single wound, as the child may have brushed up against the lit cigarette. Intentional cigarette burns, on the other hand, are typically circular in pattern; there may be multiple wounds, and the burn develop deeper into the tissue. (See Figure 2)

MEDICAL CONDITIONS WHICH MIMIC BURNS

When evaluating burns in children, it is important to know that some medical conditions can mimic these burns. Bullous impetigo, contact dermatitis, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, eczema, ingestion of laxatives and streptococcal infections can all be mistaken for burns (Miller, 2014). Impetigo, a bacterial rash that can occur on the face, hands and feet, can resemble cigarette burns. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a red blistering bacterial rash with a similar appearance to a scald burn (Miller, 2014). Laxatives containing senna can cause a caustic diarrhea that can also appear as a scald burn to the buttocks and anal area. Phytophotodermatitis is a skin reaction that can occur from a combination of the sun in reaction with citrus fruits or certain vegetables (Miller, 2014). It typically occurs approximately one hour post ingestion of the food and can appear as a scald burn.

Burns are a fairly common injury in the young child. Given the variety of potential causes and the varying degrees, evaluating burns can be a challenge. Determining whether burn result from accidental or non-accidental injury requires medical professionals to consider the whole picture and refrain from jumping to an immediate conclusion upon initial evaluation. Full physical examination of the child and a pertinent history is required to make an appropriate medical conclusion regarding the injury to determine accidental versus intentional cause.

WORKS CITED Burn Foundation (N.D.). Safety Facts on Scald Burns, retrieved from Burn Foundation. Daria, S.S. (2004). “Into Hot Water Head First: Distribution of Intentional and Unintentional Immersion Burns,” Pediatric Emergency Care, 302-310. Kennah, E. (2011, September 20). Approach to Non-Accidental Injuries, retrieved from Pediatric University of British Columbia. Krishnamoorthy, V.R. (2012, Sept-Dec). Pediatric Burn Injuries, retrieved from National Institutes of Health. Miller, A. (2014). “Burns in Child Maltreatment,” in D.A. Chadwick, Child Maltreatment (pp. 59-68). St. Louis, Mo.: STM Learning.

Phillips, B.M. (2012). “Principles of Pediatric Burn Injury,” in Pediatric Burns (p. 14). Amherst, N.Y.: Cambria Press.